Issue 23

In today’s issue, guest contributor Eric Matthew Richardson explores the partnership of Jacques Demy and Agnès Varda—the power couple behind so many french movie musicals—and the influence they had on each other’s work.

• 6.8 | We pay our respects to pop sensation and movie musical star Olivia Newton-John (Grease, Xanadu). Vanity Fair celebrates her performance in the role of Sandy. [Vanity Fair]

• 6.8 | Tom Cruise is getting his own musical. He got a taste in Rock of Ages and is hankering for more. [Deadline]

• 7.30 | Netflix sues sues creators of “The Unofficial Bridgerton Musical.” [Hollywood Reporter]

• 7.27 | Teaser for Guillermo Del Toro’s stop-motion Pinocchio musical. [YouTube]

By Eric Matthew Richardson

The World of Jacques Demy opens with a young fan reading a letter she had written to the late director years prior, thanking him for his life and work. What follows is a series of non-chronological anecdotes, each offering a sincere memory of how Jacques had changed the course of their lives. A bus driver in Nantes. A gardener who creates elaborate topiaries. Harrison Ford. It's a unique portrait of an artist told through a mosaic of reflections. But what's more fascinating than the man on the screen is the woman behind the camera. An artist who painted her subject with careful, emotional strokes—who knew her subject more intimately than anyone else. A confidant. A partner. An equal.

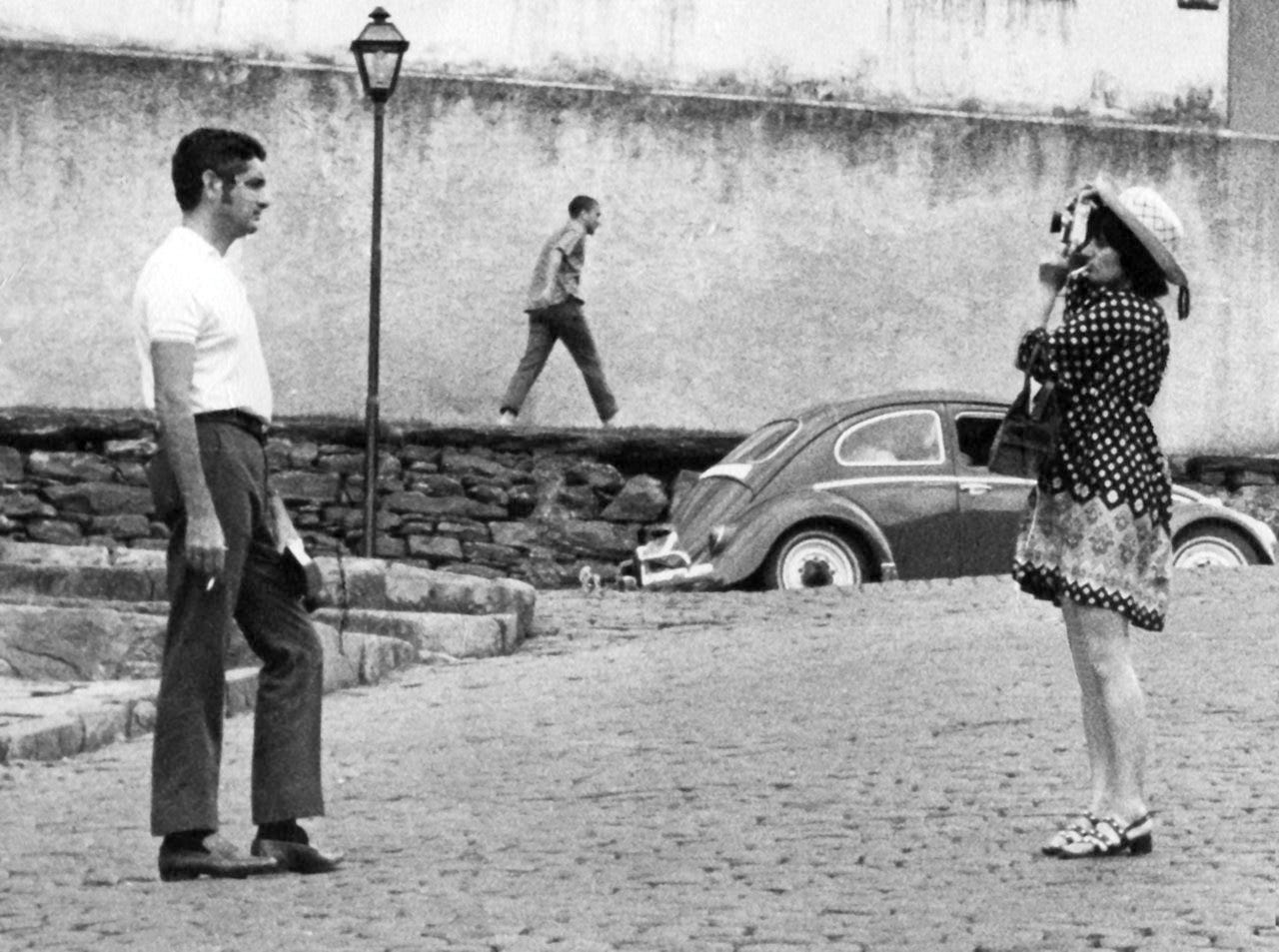

Jacques Demy and Agnès Varda met at a French film festival in 1958. Jacques, who is now celebrated as a titan of French cinema due to his lavish movie musicals, was only just beginning a solo filmmaking career after a brief period as an assistant in animation and documentaries. Agnès, however, was already somewhat of an underground icon. Her 1955 low-budget debut La Pointe Courte gained widespread critical acclaim among her peers, and is now recognized as the birth of an entire cinematic revolution. Immediately smitten with each other, they moved in together a year later and married in 1962. Together, they were determined to create a new language for film: passionate, sincere, and real.

After World War II, France focused their economic efforts on rebuilding what was lost, which left new, emerging artists without much financial support. This bred a new generation of young, scrappy filmmakers: rebellious, introspective, and above all, resourceful. The movement saw wide international popularity and influence, most notably the films of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, who began their careers as film critics in the popular magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. Calling themselves The French New Wave, they attacked their work from a critical angle, hoping to evolve the form into something new. But their perspectives were often limited to their own personal worldviews: white, male, and upper-middle class.

However, there was another group of artists that sought to broaden this lens. They used their work to discuss social issues, make political statements, and challenge their viewers to enact change. They were deemed The Left Bank - a term supposedly coined by Godard as a way to distance himself from the new socially-conscious group. This loose conglomerate featured prominent members like Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and of course, Jacques Demy and Agnès Varda. Though they frequently collaborated and shared a similar, radical taste, Varda would comment that "there was never anything more shared by the group than friendly conversation and a love of cats."

Demy's childhood was marred by the violence of the war, and he sought to recapture the magic and romance of the lavish American movie musicals in which he would frequently escape. But that was a difficult proposition in France, both critically and financially. His first full-length film, Lola, was set to be a full-on technicolor musical assault, but was pared down to a much more modest black-and-white outing on request from the producer. The result was what he referred to as "a musical without music," which borrowed the visual language of classic American musicals to tell the story of a cabaret singer and single mother who is torn between past lovers. It takes a mundane story of missed connections and what-ifs and heightens it into an operatic and bittersweet romance, a theme that would resonate throughout his work.

Varda, on the other hand, painted with a more politically charged brush. Her first film after marrying Demy, Cleo from 5 to 7, is a real-time journey through the streets of Paris as a pop singer awaits the results of her biopsy. Varda chooses not to deify Cleo as a victim, but rather as a fully-fleshed and complex person. She’s not a counter-cultural heroine who overcomes adversity. She's an ordinary woman, flawed and vain, whose quiet suffering is often dismissed or downplayed by others. It's life as it is, not as it should be. It's reflective of Varda's unique brand of no-wave feminism, stating that "I did all that—my photos, my craft, my film, my life—on my terms, my own terms, and not to do it like a man."

Upon comparison, it’s curious that these two artists were attracted to each other. One, a passionate idealist with a flair for romance, the other, a trailblazing realist with an eye for social change. And while they largely kept their work lives separate throughout their marriage, you can sense a subtle cross-pollination as their careers progressed.

Demy was given access to larger budgets, and was finally able to create the sweeping ode to the classic Hollywood musical he had always wanted to make: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. With every line of dialog sung to Michel Legrand's lush orchestrations, Demy portrays this incredible and passionate working class romance with all the color and vibrancy it deserves. Yet despite the candy-colored sets and decadent score, there's still a hint of bitterness bubbling underneath. As the film progresses and the viewer settles in to its rhythms, reality rears its ugly head. The lovers are ripped apart by an unjust war, only to reunite years after they've both moved on. As the vibrancy fades, we ache for what could have been and what could still be done. In an American musical, fate and circumstance often give rise to the realization of our dreams. But in the world of Jacques Demy, they are often tools of destruction.

While her husband pursued a highly romanticized style, Varda sought to capture her political interests through grounded features, shorts, and documentaries, even spending some time with the Black Panthers at the height of the Free Huey movement. But as her work evolved, her husband's taste for spectacle and musicality began to peek through. Her 1977 film One Sings, the Other Doesn't is a story about two friends whose lives intertwine over the course of a decade as they fight for women's liberation and abortion rights. While the film doesn't skirt away from heavier subject matter, she incorporates small musical sequences to accentuate their journey, with songs written by Varda herself.

Demy, too, began to show influence of his wife's penchant for political provocation more openly in his later work, subverting the conventions of the American musical film to create a dreamlike twist on darker subject matter. Donkey Skin, an adaptation of the classic fairy tale, explores the psychological and sexual abuse by those in positions of power. The Young Girls of Rochefort briefly interrupts his most fantastical work yet to inform the audience that the very same Lola of his previous film was recently the victim of a crazed axe murderer. But the film that most openly wears his wife’s influence is his late musical drama Un chambre en ville. Set amid the backdrop of a violent clash between a labor union and the police, the film is entirely sung-through like Umbrellas, but instead depicts a darker and tragic tale of unrequited love, poverty, and violence. It's the total inversion of the American musical palate - Foscaby way of An American in Paris.

Demy died from AIDS complications in 1990. As a bisexual man, he had separated from his wife for a brief period in the '80s. “We had trouble," Varda described, "but it was still a strong relationship. Even then we lived on opposite sides of the street. And then we got together again and felt the delight of rediscovering the other after a little break.” After his death, Varda created not one, not two, but three films about the life of her husband, showing his trademark use of nostalgia and whimsy. It was clear that their respect for each other—as friends, as lovers, and as artists—went deeper than mere admiration. They gave space for each other to live and create however they chose, but still allowed one another to affect their work.

The World of Jacques Demy ends just as it began: the same young girl reading her letter to Jacques. Only this time, we know something: the letter never reached him before his death. "You give expression to a world both true and reinvented," she reads. But just as the interview ends, Agnès slowly pans the camera onto something new: a headstone that reads Demy. It's a tender and bittersweet moment - an ending that feels right at home in the world of Jacques Demy.

Eric Matthew Richardson is a composer, writer, and sound designer based in Chicago, Illinois. Follow Eric (@TheEMRMusic) on Twitter and Instagram and check out his work at ericmatthewrichardson.com

The vast majority of Demy’s and Varda’s filmography can be watched on The Criterion Channel.

Rooster Revue is edited by Matt Andrews and Jeffrey Simon with contributions from the entire team at The Barn. Read past issues in the archive.